Billy Brown, of the Shades of Brown, brings the soulful journey of Chicago’s South Side to life in this rich interview with Bob Abrahamian on WHPK 88.5 FM. Growing up in Altgeld Gardens, Brown started in music early, drumming on coat hangers before forming a duo with his friend Chris Allen. From local talent shows to Chicago’s iconic Chess Records, his path traverses Chicago’s vibrant music scene of the 1960s and ‘70s. Alongside friends and collaborators like Maurice White and Bobby Miller, Brown’s Shades of Brown helped to shape Chicago soul through unmissable tracks like “Man’s Worst Enemy” and “Falling in Love Too Hard,” creating a timeless legacy. This dialogue captures the intensity and creativity of an era and one man’s dedication to the craft.

Bob Abrahamian 00:00

Okay, you are tuned to WHPK 88.5 FM in Chicago. You’re now listening to Sitting in the Park. My name is Bob, and today’s going to be a good show because I have a special guest: Billy Brown, a member of the Chicago group, the Shades of Brown. He’ll be talking about his recording, writing, and musical career. So definitely stay tuned. We’ve got a lot of excellent records, which we’ll be playing and discussing. First off, thanks so much for coming down to the studio.

Billy Brown 00:36

You’re more than welcome, Bob. How you doing?

Bob Abrahamian 00:38

Doing well! So, first of all, can you talk about whether you’re originally from Chicago?

Billy Brown 00:44

Yes, I am originally from Chicago, the South Side.

Bob Abrahamian 00:47

What specific area are you from?

Billy Brown 00:49

I grew up in the Altgeld Gardens area.

Bob Abrahamian 00:54

How did you originally get involved with music?

Billy Brown 00:58

Wow, how much time you got?

Bob Abrahamian 01:01

We've got 90 minutes!

Billy Brown 01:05

Well, I started like a lot of performers—singing in church and playing drums at a very early age, around seven or eight.

Bob Abrahamian 01:17

How did you get into drums that early?

Billy Brown 01:20

Just beating on everything—pots and pans. I eventually had a set that was mostly a large marching band bass drum, and I’d play it with the side of my foot since I didn’t have a pedal. I tore up a lot of my mom’s coat hangers, using them as drumsticks. Thankfully, I met Christopher Allen around sixth grade. We met through my brother Andrew, whom we call “Dre.” Chris and I became best friends. Chris played guitar and sang, and we started joining forces, doing talent shows all over the city.

Bob Abrahamian 02:15

So, Chris was also from the Gardens?

Billy Brown 02:18

Yes, he was. We formed a duo before high school and performed together. My brother joined us briefly, but then we added other members, like Andre Bell, who’s now a dean at Northwestern, and Carolyn Selman, now a business entrepreneur.

Bob Abrahamian 02:48

What year was it when you were just starting out in sixth grade?

Billy Brown 02:52

Early 60s. Actually, maybe even late 50s, but mostly early 60s.

Bob Abrahamian 03:02

Were there other groups from the Gardens that inspired you?

Billy Brown 03:09

Yes, there were so many groups and individual artists. The most well-known group from the 50s was the Debonaires. We were fortunate to be around them—Ralph and all of the Debonaires, George Vineyard, Odell Carter, who was related to Otis Clay. These were people from the community whom we saw every day.

Bob Abrahamian 03:58

By sixth grade, you were already a duo, and Chris Allen is also Chris Bernard, right?

Billy Brown 04:05

Yes, correct. Chris sang and played guitar, while I played drums. My dad bought my younger brother Charles a guitar that he never played, so I asked Chris to show me chords, and we started doing duets on the guitar—Everly Brothers songs and such.

Bob Abrahamian 04:33

When you say you were touring, what kind of venues did sixth graders play in Chicago?

Billy Brown 04:39

A lot of talent shows. We often came in first or second place in those.

Bob Abrahamian 04:46

Did you have a name for your band back then?

Billy Brown 04:49

We went by different names over time: the Four Trails, the Mentors—although that came a bit later. Initially, we were just “Chris and Bill.”

Bob Abrahamian 05:11

And how did you move from a duo to forming a full band?

Billy Brown 05:17

It started as a vocal group, but we were mostly accompanying ourselves.

Bob Abrahamian 05:26

Did the full band form when you were in high school?

Billy Brown 05:30

Yes, just before high school. We added members like Catherine Selman, Andre Bell, and Charles Scott. A few others came in and out.

Bob Abrahamian 05:43

Did you all go to the same high school?

Billy Brown 05:47

Yes, Harper High School. There were a lot of groups there, including Little Ben and the Cheers, who were the children of the Norfleet Brothers, a renowned gospel group. Pattie and the Love-Lites also came from Altgeld Gardens.

Bob Abrahamian 06:08

Were you a bit older than the Love-Lites?

Billy Brown 06:10

Yes, we were. Chris actually helped them get recorded. Pattie and her family lived right across the street from me.

Bob Abrahamian 06:18

So by high school, you had formed a band. What was your initial band name?

Billy Brown 06:33

The first name we went by was the Four Trails.

Bob Abrahamian 06:36

Was that one word or two?

Billy Brown 06:38

One word: Trails.

Bob Abrahamian 06:39

How did you come up with that?

Billy Brown 06:44

We were just sitting around, brainstorming. That was years ago, so I can’t quite remember how it came about, but we settled on it.

Bob Abrahamian 06:55

Did your band continue doing talent shows and such?

Billy Brown 06:57

Yes, we did a lot of talent shows.

Bob Abrahamian 06:59

Eventually, your group got a record deal. What was the first label you worked with?

Billy Brown 07:13

We started with St. Lawrence Records, then went to Wonderful Records.

Bob Abrahamian 07:18

How did that come about?

Billy Brown 07:22

Chicago was a huge music scene back then. People referred to it as the number one record market. WVON, known as “The Voice of the Negro,” was a community-based station that played Chicago music—soul music you couldn’t hear on other stations.

Bob Abrahamian 08:02

Did you sign with St. Lawrence before Wonderful?

Billy Brown 08:04

Yes, St. Lawrence came first.

Bob Abrahamian 08:16

Did someone introduce you to St. Lawrence?

Billy Brown 08:17

Yes, Monkey Higgins introduced us. It was common to meet so many people in the industry if you were involved. Eventually, we ended up recording for ABC Records in California and drove there with Higgins in his new Cadillac.

Bob Abrahamian 09:00

Did you record anything at St. Lawrence?

Billy Brown 09:02

No, but we recorded one track at Wonderful. Otis Clay later re-recorded it.

Bob Abrahamian 09:21

How did you end up at Wonderful?

Billy Brown 09:24

I don’t recall exactly how, but we knew a lot of people at that time.

Bob Abrahamian 09:44

So you transitioned from the Four Trails to the Mentors, correct?

Billy Brown 09:54

Yes, that was when we signed with ABC Records.

Bob Abrahamian 09:59

How did you get connected to ABC Records?

Billy Brown 10:01

I met Barry Despenza, who became a close friend and my writing partner. Barry wrote Can I Change My Mind for Tyrone Davis.

Bob Abrahamian 10:18

He produced some Tyrone records at ABC, right?

Billy Brown 10:20

Yes, and he recorded four tracks with my group, though they were never released.

Bob Abrahamian 10:29

So, were you just out of high school when you signed with ABC?

Billy Brown 10:34

Just barely. We were working part-time and performing often, managed by Herman Williamson and Sylvia Taylor. Herman ran the Regal Theater, where I worked as an usher and later as staff until the theater closed.

Bob Abrahamian 11:18

And you said you recorded four sides as the Mentors for ABC?

Billy Brown 11:25

Yes, four sides, but they were never released. Maurice White of Earth, Wind & Fire played drums on that session, which was amazing.

Bob Abrahamian 12:32

So, you recorded four sides as the Mentors at ABC in around ’68 or ’69?

Billy Brown 12:39

Yes, that’s right.

Bob Abrahamian 12:41

And what was the lineup of the group at that point?

Billy Brown 12:49

At that time, it was Chris Allen, Charles Scott, Arthur Williams, and myself, William Brown. So we were a four-man group then.

Bob Abrahamian 12:55

So you recorded four sides for ABC, but due to legal issues, they weren’t released?

Billy Brown 13:09

Exactly. It was frustrating. We put a lot of work into those tracks and worked with incredible musicians like Maurice White, who played drums on the session, and Fred Ware, who helped produce and arrange. It was a session like no other.

Bob Abrahamian 13:37

Do you remember the studio where you recorded the ABC material?

Billy Brown 13:43

At this point, I can’t recall the exact studio.

Bob Abrahamian 13:47

So, after the ABC sides remained unreleased, you signed with another label?

Billy Brown 13:57

Yes, we moved from ABC to Chess Records.

Bob Abrahamian 14:04

How did that come about?

Billy Brown 14:06

We met Bobby Miller through mutual connections. Years back, we had recorded with Leo Austell in his basement, but it wasn’t released. Eventually, we met Billy Davis, Jr., who was A&R at Chess at the time. Billy briefly managed us before he left Chicago for Motown, where he produced the famous Pepsi jingle, I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing. Later, Bobby Miller and I, who were already good friends, became writing partners.

Bob Abrahamian 14:59

Bobby Miller, known for his work with the Dells, right?

Billy Brown 15:03

Yes, and also for If Walls Could Talk for Little Milton. He even released a few solo records.

Bob Abrahamian 15:20

So Bobby Miller became your producer and manager at Chess?

Billy Brown 15:24

Yes, that’s right.

Bob Abrahamian 15:32

Did you change your group’s name again when you signed with Chess?

Billy Brown 15:39

Yes, we became the Shades of Brown. Bobby and I decided on that name together.

Bob Abrahamian 15:43

And did the lineup change when you joined Chess?

Billy Brown 15:48

Yes, a bit. Clarence Johnson introduced us to Earl Roberts, who joined the group. At one point, we were five members, but there was some friction, and Chris left. So the Shades of Brown became Earl Roberts, myself, Arthur Williams, and Charles Scott.

Bob Abrahamian 16:13

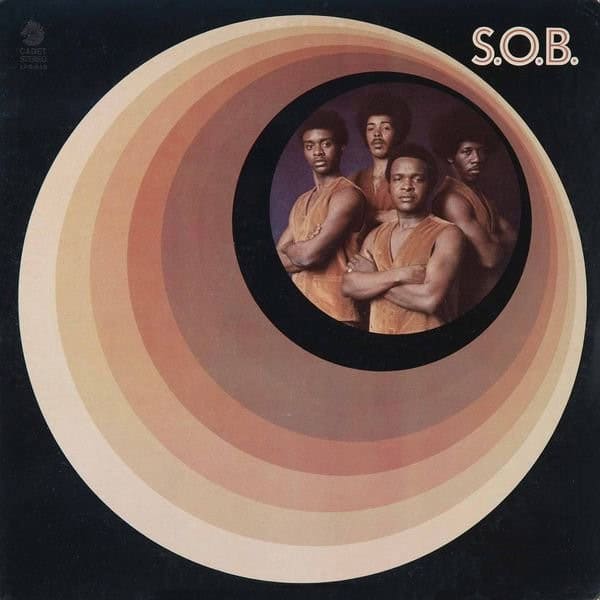

So that’s the lineup on your Cadet album?

Billy Brown 16:15

Correct. That’s the lineup for our album on Cadet.

Bob Abrahamian 16:19

Alright, let me play one of the tracks from your Cadet album, Little Girl. We can discuss how this recording came about afterward.

[music playing: “Little Girl” by Shades of Brown]

Bob Abrahamian 18:26

That was the Shades of Brown with Little Girl, one of the tracks released on Cadet Records, a division of Chess. If you’re just tuning in, I have Billy Brown, lead singer of the Shades of Brown, with me in the studio. So, we were just discussing your time at Chess, where Bobby Miller was your manager. That track has a bit of a Dells influence, with the harmonies and backing. Would you say that Bobby helped shape your sound?

Billy Brown 19:14

I would say so. Bobby and I were writing partners. I’d be at his place just about every day, guitar in hand, and we’d work on structuring songs together. I was also blessed with an ear for harmonies, so I would work out the harmonies with the guys alongside Bobby.

Bob Abrahamian 19:41

Did you know the Dells personally?

Billy Brown 19:42

Yes, all of the Dells were great friends. Through marriage, I ended up related to Marvin Junior’s and Mickey McGill’s families.

Bob Abrahamian 19:57

What was the first single that Cadet released?

Billy Brown 20:02

The first single was Man’s Worst Enemy, and Little Girl was on the B-side.

Bob Abrahamian 20:11

Did Man’s Worst Enemy get a lot of play in Chicago?

Billy Brown 20:16

Yes, it did. It got a lot of airplay locally.

Bob Abrahamian 20:20

So you were on the Cadet label, which had a lot of rock and psychedelic acts, like Rotary Connection. Did you ever feel the label wanted you to cross over to a wider, maybe white audience?

Billy Brown 20:56

I never thought about it that way, but looking back, I can see that influence. At the time, we were just focused on making good music.

Bob Abrahamian 21:12

When you say it was a hit, did it get play on R&B radio?

Billy Brown 21:22

Yes, on R&B stations. I don’t know if it crossed over to stations like WLS, but I know it had international reach. People would show me copies of our album they had bought in Japan and other places.

Bob Abrahamian 21:37

So, did the singles come out before the album?

Billy Brown 21:46

Yes, Man’s Worst Enemy came out as a single before the album.

Bob Abrahamian 21:53

And the second single—was it Ho Hum World?

Billy Brown 21:59

Yes, Ho Hum World came after Man’s Worst Enemy, with Garbage Man as our final single.

Bob Abrahamian 22:07

Did you start doing more shows as the Shades of Brown?

Billy Brown 22:12

We did. We toured nearly every state in the U.S.

Bob Abrahamian 22:17

Did you do a revue with other Chess artists or just the Shades of Brown?

Billy Brown 22:24

Mainly, we did our own revue. At one point, we had about 25 people in our show, including a band called Eyepieces, Breakwater, and the Shades of Brown Review.

Bob Abrahamian 22:29

Were your band members also from the Gardens?

Billy Brown 22:33

No, they were from all over the city. We had Lee Simmons on organ, Jerry Holmes on congas, and other fantastic musicians.

Bob Abrahamian 22:50

Who were some of the big acts you performed with on tour?

Billy Brown 22:57

We played with James Brown and many others. I can’t remember all the names, but we did a lot of shows.

Bob Abrahamian 23:21

Did you still perform a lot in Chicago?

Billy Brown 23:32

Yes, we played at clubs like Mr. Kelly’s, Russell’s, Roberts 500 Room, the Auditorium Theater, and the Arie Crown Theater.

Bob Abrahamian 23:39

Alright, let me play another track from the album, one that wasn’t released as a single. This one is called Line Number Two.

[music playing: “Line Number Two” by Shades of Brown]

Bob Abrahamian 27:57

You’re listening to WHPK 88.5 FM in Chicago. That was the Shades of Brown with Line Number Two off their 1970 self-titled album on Cadet. We’re here with Billy Brown, lead singer of the Shades of Brown, talking about the group’s journey. So, we were discussing your tours and your releases on Cadet. Did you record anything else at Cadet that wasn’t released?

Billy Brown 28:40

No, everything we recorded there was released.

Bob Abrahamian 28:43

How did you end up leaving the label?

Billy Brown 28:47

Well, after the album’s international release, Leonard Chess, who was the heart of the company, passed away. That loss hit the company hard, and a lot of key people started leaving—like Bobby Miller, who moved to Motown. The musicians who played on our records, like Earth, Wind & Fire members, all went to California, and that was it for Chess.

Bob Abrahamian 29:52

So Bobby Miller left Chicago for Detroit. Did that leave you without a manager and producer?

Billy Brown 30:01

Yes, it did. Without work, group dynamics started breaking down. Disco was coming in, and live entertainers were being replaced by DJs.

Bob Abrahamian 30:27

You recorded another single on the On Top label, How Could You Love Him? How long after Chess did that come out?

Billy Brown 30:45

Not too long after. Man’s Worst Enemy and Falling in Love Too Hard were big off the Cadet album, but soon after, we worked with Calvin Carter on How Could You Love Him? on the On Top label.

Bob Abrahamian 31:09

Calvin Carter produced that single. How did you know him?

Billy Brown 31:12

Through the industry. Calvin was Vivian Carter’s brother, co-owner of Vee-Jay Records. Everyone in the music scene knew each other.

Bob Abrahamian 31:42

Did he manage you at that time?

Billy Brown 31:44

No, but he wanted to produce He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother, with Arthur Williams on vocals. Unfortunately, Arthur passed away later. I wrote How Could You Love Him? as the flip side.

Bob Abrahamian 32:19

So, How Could You Love Him? wasn’t meant to be the A-side?

Billy Brown 32:23

No, but it ended up that way.

Bob Abrahamian 32:27

Alright, let me play How Could You Love Him?—my favorite track from the group.

[music playing: “How Could You Love Him?” by Shades of Brown]

Bob Abrahamian 35:00

You’re tuned to WHPK 88.5 FM in Chicago. That was the Shades of Brown with How Could You Love Him?, released around 1971 on the On Top label, produced by Calvin Carter. Did that record get any play in Chicago?

Billy Brown 35:54

Not much, maybe the wrong side was promoted.

Bob Abrahamian 35:57

You were labelmates with Bobby Rush. Did you know him?

Billy Brown 36:08

Yes, Bobby and I were good friends and even wrote together. We performed together in New Orleans and Arkansas.

Bob Abrahamian 36:30

Did you ever release any songs with Bobby Rush?

Billy Brown 36:35

No, unfortunately, we didn’t.

Bob Abrahamian 36:51

So, How Could You Love Him? ended up being the last single the Shades of Brown released. Was there any unreleased material from the group?

Billy Brown 37:04

Yes, actually, quite a bit. We recorded four tracks with Clarence Johnson, who also managed acts like Brighter Side of Darkness and Pattie and the Love-Lites.

Bob Abrahamian 37:11

Was that before or after you recorded How Could You Love Him??

Billy Brown 37:14

It was actually just before that single.

Bob Abrahamian 37:19

You mentioned one of the unreleased tracks was a song called Love Like the Seasons. I was telling you earlier that the Five Wagers recorded a version of that song.

Billy Brown 37:23

Yes, I didn’t even know that until you mentioned it. It’s very obscure. Love Like the Seasons was written by Mickey Farrell, who co-wrote Catfish for the Four Tops. Mickey and Rodney Massey were a writing team who worked with Jerry Butler’s writing workshop, which was where we recorded the track. Mickey was incredibly talented, both as a singer and a songwriter.

Bob Abrahamian 38:19

Mickey and Rodney were quite prolific. The last interview I did was with Buck Ray Buckner, and Ben Wright, who also did arrangements for your group, did strings on Buck’s record too.

Billy Brown 38:25

Yes, Ben Wright was amazing. He later went on to write One Hundred Ways for James Ingram and is now Gladys Knight’s musical director. Ben also worked with other legendary artists and was a musical conductor for Chess.

Bob Abrahamian 38:43

Did you record any other unreleased tracks besides those with Clarence Johnson and the earlier ABC material?

Billy Brown 38:47

No, that was most of the unreleased work. After we disbanded, I started other projects.

Bob Abrahamian 39:00

How long did the Shades of Brown stay together after that?

Billy Brown 39:04

Not long after we recorded those last tracks. Initially, Bobby had talked about us getting our own studio, and we started working on a building on Calumet. It eventually became PS Recording Studio, owned by Paul Serrano, a premier trumpet player at Chess. We were all good friends, so we helped him get it ready, tearing down walls and everything. But shortly after that, we had some internal issues, and the group disbanded. Paul kept the studio going.

Bob Abrahamian 39:33

So this was in the mid-70s?

Billy Brown 39:34

Yes, around that time.

Bob Abrahamian 39:42

But you continued in music afterward, right?

Billy Brown 39:47

Yes, I did. After the Shades of Brown, I started a project with Cheryl Swope, a fantastic vocalist. Cheryl came from a group called Two on Coming Time, and we began performing as a duo, opening for acts like Walter Jackson and others at venues like the High Chaparral.

Bob Abrahamian 40:11

So you and Cheryl performed as a duo, sort of like a Donny Hathaway and Roberta Flack type of thing?

Billy Brown 40:17

Yes, exactly. Ronnie Jones named us “Two.” So we were simply known as “Two.”

Bob Abrahamian 40:21

Did you perform as “Two” around Chicago?

Billy Brown 40:24

Yes, we did. This was in the late 70s and early 80s. We performed as a duo all the way up until 1983.

Bob Abrahamian 40:36

Did you and Cheryl record anything as “Two”?

Billy Brown 40:41

Yes, we did, but unfortunately, it was never released.

Bob Abrahamian 40:44

Was it a home recording, or did you go to a studio?

Billy Brown 40:47

We went to a studio. Some of the recordings were arranged by Tom Tom and Ben Wright, who were also involved in other Shades of Brown projects.

Bob Abrahamian 40:59

Was there a specific label you were aiming for with those recordings?

Billy Brown 41:06

Yes, Cheryl and I signed with All Platinum Records, out of Englewood, New Jersey, which was owned by Joe Robinson and Sylvia. They had artists like Ray, Goodman & Brown, the Moments, Brook Benton, and Linda Jones on the label.

Bob Abrahamian 41:30

There was even a Chicago artist on All Platinum in the late 70s—Jimmy Mays and the Mill Street Depot. Did you know Jimmy?

Billy Brown 41:32

Yes, we crossed paths with him. So there was a small Chicago connection to All Platinum. Unfortunately, our work with them never got released. They recorded a lot of material that was never put out.

Bob Abrahamian 41:58

Did you continue doing music after the early 80s, once Cheryl and you parted ways?

Billy Brown 42:02

Yes, Cheryl got married, so we went our separate ways. She had other commitments, but we did a few more recordings at Oakwood Studios, south of Chicago. That was the last of our recordings together. After that, I started working solo.

Bob Abrahamian 42:24

What kind of music projects did you do in the 80s and 90s?

Billy Brown 42:32

By then, I had picked up a lot of skills from being around artists like Curtis Mayfield and learning about studio technology. Being a drummer, guitarist, and keyboard player, I started recording my own tracks at home.

Bob Abrahamian 42:52

So you were doing home recordings at that time. You had mentioned a band called Vibes. Were you in that band during the 80s?

Billy Brown 43:00

Yes, Vibes was a band that Cheryl and I performed with as well. We did shows at the Forum in New York, the Arie Crown Theater, Mr. Kelly’s, Russell’s, and the Roberts 500 Room, which was popular back then.

Bob Abrahamian 43:17

Are you still involved in music today?

Billy Brown 43:21

Absolutely. I am currently a music director and instructor for the City of Chicago, working with the Chicago Park District.

Bob Abrahamian 43:30

What does that entail? Are there specific events, or is it more day-to-day lessons?

Billy Brown 43:36

I primarily teach kids how to play instruments. We offer music lessons for piano, drums, and guitar through the city.

Bob Abrahamian 43:45

And you help organize music events for the city too?

Billy Brown 43:49

Yes, I’m one of the music directors for the South Region, so I’m involved in a lot of events, like the African Festival and various music events throughout the year.

Bob Abrahamian 44:02

What lessons do you teach?

Billy Brown 44:05

I teach piano, drums, and guitar.

Bob Abrahamian 44:12

Alright, let me play one more track from the Cadet album, one that got a lot of play. This one is called Falling in Love Too Hard.

[music playing: “Falling in Love Too Hard” by Shades of Brown]

Bob Abrahamian 47:02

You’re tuned to WHPK 88.5 FM in Chicago. That was the Shades of Brown with Falling in Love Too Hard. If you’re just tuning in, I’m here with Billy Brown, who’s been sharing stories about his musical career. Thank you so much for coming down and sharing these memories.

Billy Brown 48:18

You’re more than welcome, Bob. It’s been a pleasure.

Bob Abrahamian 48:23

Do you have any last words for the listeners?

Billy Brown 48:36

I’m just grateful for the opportunity. Growing up in Altgeld Gardens, I was blessed to be around so many legendary artists—from Jimmy Reed to Bo Diddley to Curtis Mayfield. Being part of that scene and later getting to work with people like Maurice White and Bobby Miller was a blessing. It’s incredible how many people don’t know my background in music, even those I grew up around.

Bob Abrahamian 49:22

Thank you again for sharing your story.

Billy Brown 49:24

Thank you for having me, Bob.

Bob Abrahamian 49:27

Alright, we’re going to close out with one more track, which I believe was your first big single, Man’s Worst Enemy.

[music playing: “Man’s Worst Enemy” by Shades of Brown]