How Bernice Watkins and Living Color Lit Chicago’s Soul Scene!

From Cabrini Green’s red-brick towers to the soulful corridors of Brunswick Records, Bernice Watkins’ story offers a vivid lens into the rise of Chicago’s homegrown soul scene in the late 1960s. As a founding member of Living Color, Watkins and her bandmates channeled gospel roots, vocal prowess, and local pride into a singular sound. Though Living Color never secured a contract, their track “Thank the Lord for Love” remains a prized gem in the Northern Soul movement—proof that even one single can echo across decades and oceans.

In the great oral tradition of soul music history, some stories shimmer more quietly but carry equal weight in their cultural resonance. One such voice belongs to Bernice Watkins, who came of age in the mid-20th century amid the dense, defiant vitality of Chicago’s Cabrini Green housing projects. Her interview with Bob Abrahamian on Sitting in the Park is more than a personal reflection—it’s a testimony to how grassroots soul artistry took root far from the national spotlight, shaping the sound of a city and leaving fingerprints on movements still rippling worldwide.

Living Color: A Name, A Mission, A Harmony

Born out of high school choir halls and church pews, Living Color emerged from a uniquely Black, female perspective on Chicago’s North Side. Watkins, alongside Bertha Coleman and Janet Miles, founded the group at Cooley High. Their vocal blend—anchored in gospel training and refined through disciplined rehearsals at home, school, and local haunts like Poor Richard’s—was driven by genuine love for the craft, not commercial ambition.

The group’s name was both literal and metaphorical. “We were different shades of Black,” Watkins told Abrahamian, “and we didn’t want to go with something like ‘Shades of Black.’” Instead, they coined Living Color—a prescient assertion of visibility, agency, and pride at a time when Black women were often forced into the musical background.

Recording Without Recognition: Brunswick and Beyond

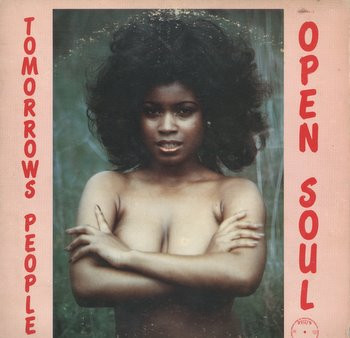

In a city brimming with label activity—Curtom, Twinight, One-derful, and of course, Brunswick—Living Color’s break came in the form of a local talent show judged by soul stalwart Barbara Acklin. Competing against groups like The Emotions, they won—and Acklin, impressed, brought them to Brunswick. There, they recorded the poignant “Thank the Lord for Love” and its flip side “Got a Strange Feeling.”

The tracks were released on Mad Hatter Records, a smaller imprint distributed through Brunswick. While they never charted commercially, the single later gained traction in the UK’s Northern Soul circuit, a testament to its rhythmic urgency and emotive depth. Watkins’ contralto voice—grounded, rich, and unshakeable—gave the track a spiritual center, while the harmony work demonstrated the group’s disciplined choir upbringing.

But industry barriers and interpersonal tensions unraveled their path before it could fully form. Bertha’s boyfriend disapproved of her involvement, and Janet lost motivation. Watkins remained ready, but couldn’t carry the group alone. In a particularly bitter turn, the name Living Color was used elsewhere without the trio’s permission, a sadly familiar tale for many Black artists of the era whose intellectual and creative property was often co-opted without recompense.

Behind the Scenes and Backing Legends

Even as Living Color faded from public view, Watkins’ voice remained omnipresent in Chicago soul’s engine room. Starting at just 14, she provided background vocals at Brunswick, supporting legends like Jackie Wilson, Gene Chandler, Barbara Acklin, and The Chi-Lites. “Whoever needed background vocals, we were there,” she said matter-of-factly—though her contribution was anything but ordinary.

Like so many unsung session singers—particularly Black women—Watkins' work powered iconic records while her name stayed off the sleeve. It wasn’t until she toured the South on college gigs and recorded solo standards decades later that she stepped into her own spotlight.

A Soul Survivor’s Second Act

By the mid-1970s, Watkins had stepped back from music. “Drugs were everywhere,” she noted. “I didn’t want that.” Instead, she raised a family, finding her way back into music in the 1990s as Bonnie Watts, a jazz and blues singer with a Latin band in Albuquerque.

Her modern repertoire includes jazz standards like “Summertime” and an original piece titled “We Bleed Red Blood,” co-written with Doug Shorts. The song is a reflection on resilience, emotional pain, and female strength—echoing the lived experience of a woman who’s seen music, and life, from every side of the mic.

Legacy in Living Color

What makes Bernice Watkins’ story especially vital is its ordinariness within the extraordinary. She never reached stardom, yet her voice was part of a foundational wave of Chicago soul. Her story illuminates the thousands of other women who, like her, balanced school, jobs, motherhood, and personal struggle while carving out musical space in a male-dominated industry.

And while the charts may not have preserved Living Color’s name, Northern Soul collectors have. In the UK dancehalls where DJs spin deep cuts and rare grooves, “Thank the Lord for Love” continues to echo—an anthem of overlooked talent and timeless emotion.

Interview with Bernice Watkins (Living Color) on WHPK 88.5 FM - Sitting in the Park

Bob Abrahamian: Okay, you are tuned to WHPK 88.5 FM in Chicago. You're now listening to the Sitting in the Park show. Today is a special show, because we’ll be starting with an interview with a singer from a female group from the North Side of Chicago named Bernice Walker. Bernice, can you hear me?

Bernice Watkins: Yes. Okay. It’s Bernice Watkins.

Bob Abrahamian: I'm sorry, I've already messed up your name! It’s already going bad. Sorry about that. So first of all, the group you sang with was called Living Color, is that right?

Bernice Watkins: Yes, it was.

Bob Abrahamian: Are you originally from Chicago?

Bernice Watkins: Yes, I am. From the West Side of Chicago. I moved to the North Side in '66 and have been there, in Cabrini Green.

Bob Abrahamian: Okay. How did you get started singing?

Bernice Watkins: Well, I started singing at church. You know how everyone says they started in church—I did too. I sang at New Hope Missionary Baptist Church on the North Side, right across from 660. Marvin Yancy was our music director. Then I went to Cooley High, where I sang in the choir under Miss Beatenfield with Janet Miles and Bertha Coleman. We decided to form a group.

Bob Abrahamian: Was that the first group you sang with?

Bernice Watkins: No, it wasn’t. I sang with a group in 660 when I was in sixth and seventh grade. We performed in lounges around the city. Bucha and Tony Gaines were part of it. Their parents would take us to clubs—we’d sing, they’d sit in the corner, and afterward we’d leave.

Bob Abrahamian: Were you already living on the North Side then?

Bernice Watkins: Yes, I was living at 660 West Division.

Bob Abrahamian: Was that group made up of kids your age?

Bernice Watkins: Some were older. Tony Gaines and I were the same age. His sister, Johnny May, also sang with us.

Bob Abrahamian: Do you remember what that group was called?

Bernice Watkins: I don’t think we even had a name.

Bob Abrahamian: Was it exciting to perform at clubs at that age?

Bernice Watkins: All I cared about was singing. I wasn’t thinking about the rest.

Bob Abrahamian: When you started high school, what year was that?

Bernice Watkins: I was a freshman in 1966 and graduated in 1970.

Bob Abrahamian: Who were the members of Living Color?

Bernice Watkins: Bertha Coleman (soprano), Janet Miles (alto/second soprano), and I was the contralto. I sang all parts.

Bob Abrahamian: How did the group form?

Bernice Watkins: We were in choir together. I was always in the middle because I could hold my note even with different voices on either side. One day I said, “Let’s start a group.”

Bob Abrahamian: Who came up with the name Living Color?

Bernice Watkins: We did. We were different shades of Black and didn’t want to go with something like “Shades of Black.” So we came up with Living Color, to reflect our diversity.

Bob Abrahamian: Can you talk about Cooley High and the talent shows?

Bernice Watkins: We had a Wawa Tasty Show every year with many performers from different schools—not just Cooley. It wasn’t a competition, more a showcase. Our group sang “Old Man River” to show off our vocal range.

Bob Abrahamian: Did people react well?

Bernice Watkins: Yes, very well. We performed every year.

Bob Abrahamian: Do you remember other groups from that time?

Bernice Watkins: I knew people more than group names—Doug Short, Carolyn Love, Key Stop Samuels. The Childs brothers, from the group The Admirations, lived in 1230 Burling, I think.

Bob Abrahamian: Did the other members of Living Color also live in Cabrini Green?

Bernice Watkins: Yes. Bertha lived in the red-brick buildings, Janet in the white-brick ones.

Bob Abrahamian: Where did you rehearse?

Bernice Watkins: At each other’s houses, at school, and at a place called Poor Richard’s, where we also performed.

Bob Abrahamian: How did the record “Thank the Lord for Love” come about?

Bernice Watkins: We entered talent shows, including one with Barbara Acklin. We competed against The Emotions and others—and we won. Barbara took us to Brunswick Records. They liked us and offered to record a demo. We did both sides: “Thank the Lord for Love” and “Got a Strange Feeling.”

Bob Abrahamian: Was this before or after graduation?

Bernice Watkins: It was during our senior year.

Bob Abrahamian: Where did you record the songs?

Bernice Watkins: “Thank the Lord for Love” at Brunswick, the other side at ABC Records.

Bob Abrahamian: It came out on Mad Hatter Records?

Bernice Watkins: Yes, under Mark Davis. Brunswick owned the rights and handled distribution. We wrote the songs together, but only some people were credited.

Bob Abrahamian: Why didn’t you sign a contract?

Bernice Watkins: There was tension. Bertha’s boyfriend didn’t want her in the group. Janet got frustrated. I was ready, but alone I couldn’t do much. The name Living Color was taken and used without us.

Bob Abrahamian: Did you keep singing?

Bernice Watkins: Yes. I did background work at Brunswick from age 14. We sang behind Jackie Wilson, Gene Chandler, Barbara Acklin, the Chi-Lites. Whoever needed background vocals, we were there.

Bob Abrahamian: Did you get paid?

Bernice Watkins: Eventually, yes. At first it was for experience. Later they gave me money to cover transportation and such.

Bob Abrahamian: Did the other members of Living Color continue music?

Bernice Watkins: Not really. Bertha’s boyfriend had other plans for her, and Janet lost interest. I kept doing background work. Eventually, I toured with different artists.

Bob Abrahamian: Do you remember some?

Bernice Watkins: We worked with Finis Henderson, Barbara Acklin, and others—mostly college gigs in the South. I toured until about 1975.

Bob Abrahamian: Then what happened?

Bernice Watkins: Drugs were everywhere. I didn’t want that, so I stepped back and focused on raising my kids.

Bob Abrahamian: Did you return to music later?

Bernice Watkins: Yes, in the ’90s. I sang jazz and blues in Chicago, and eventually moved to Albuquerque in 2005, where I still perform.

Bob Abrahamian: Do you go by Bernice still?

Bernice Watkins: My stage name is Bonnie Watts. “Bernice” felt too formal. I perform jazz, R&B, and some blues. I’m with a Latin band—I'm the Black singer in the group.

Bob Abrahamian: Are you recording now?

Bernice Watkins: We’re recording standards like “Summertime.” I also wrote a piece called “We Bleed Red Blood” with Doug Shorts. It’s about how women don’t just bounce back—we break.

Bob Abrahamian: Thank you for sharing your story. You may not have had a major hit, but your record is big in the Northern Soul scene in the UK.

Bernice Watkins: I’ve heard that! I’d love to go overseas.

Bob Abrahamian: Any last words for listeners?

Bernice Watkins: This is not a trial run. This is it. If you’ve got a dream, do it. That’s it.